Check this link for a top 100 sci fi shows. The top 25 are:

25. Terminator series

24. Prisoner

23. Cowboy Bebop

22. Space 1999

21. Hitchiker's Guide to the Galaxy

20. Farscape

19. V

18. Fringe

17. Stargate SG-1

16. Dollhouse

15. The Tick

14. Futurama

13. DS9

12. Twilight Zone

11. Blake's 7

10. Lost

9. BSG reboot

8. Babylon 5

7. X Files

6. Buffy

5. Max Headroom

4. TNG

3. Firefly

2. Doctor Who

1. Star Trek

My take on the top 25: Overall, this is one of the best of these lists I've seen, though none can be perfect. Firefly I think is rated a little high, though it certainly should be in the top 20, perhaps the top 10. Max Headroom I've not seen, but I'm not quite sure it's a top 10 show, at least in influence. I have no interest in Buffy or Lost, but I admit they may be good shows. It's good to see Blake's Seven and Babylon 5 high on the list. Twilight Zone should obviously be higher, as it is one of the most influential genre shows ever. Farscape too, is rated way too low, as is the Prisoner (the Prisoner should have a real shot at the top 5, both in terms of quality and genre influence). The only real problems I had with the picks was the inclusion of the Tick and Space 1999 in the top 25. The latter, in particular, is nowhere near as good as some of the other series on the list. Also problematic for me is Stargate's position, as I simply did not find it to be a quality show. I'd actually rate Andromeda and Enterprise above it. As for Star Trek and Doctor Who winning the top spots, here's my take. I certainly don't think they're the best series ever aired: Firefly, Babylon 5, BSG, Farscape, The Prisoner, and Max Headroom all had better writing. But in terms of genre influence, they are simply indispensable. I think in the future BSG and B5's influence will lead them to be rated higher in such polls (4th and 3rd respectively). However, I think Blake's Seven, arguably more influential than any series on the list save Star Trek, will never receive its due, because fans don't realize how much Firefly, Farscape, Andromeda, and Babylon 5 borrowed from it.

Friday, January 15, 2010

Thursday, January 14, 2010

The collapse of TV Sci-Fi

Excellent article on television science fiction that basically reaches the same conclusion that I have: the golden age of TV-sci fi is over. Nowdays, the genre is dominated almost exclusively by the Sci-fi Channel, a network not known for its propensity for risk. Television science fiction is instead dominated by cheap knock off series, like Stargate Atlantis, quasi-sci Fi like Heroes and Lost, and the occassional gem, like the new Battlestar Galactica. The space opera, as it stands, is practically dead. The last genuine human-alien space opera is now six years old (Enterprise) and the last great space opera (Farscape) even older. So, fans, I suspect it will be a while before we get another five year story arc, if ever.

Labels:

Babylon 5,

Battlestar Galactica,

Enterprise,

Farscape,

story arc

Battlestar Galactica and slave labor

(Image from Wikipedia) The rebooted Battlestar Galactica is one of the first sci-fi series to address slave labor in a meaningful way. Other shows had attempted to show the brutality of such systems, notably Babylon 5 and Blake's 7, but these shows could only mention that brutality in passing. But in the Battlestar Galactica episode "Bastille Day," the connection between the U.S. labor force and the use of prison populations as indentured servants is made graphically clear. Zarek is a terrorist\freedom fighter who is opting to oppose the government, purportedly out of principle, but his opponents claim he is a man obsessed with power. Here is a description of Zerek's political platform, from the episode "Colonial Day"

(Image from Wikipedia) The rebooted Battlestar Galactica is one of the first sci-fi series to address slave labor in a meaningful way. Other shows had attempted to show the brutality of such systems, notably Babylon 5 and Blake's 7, but these shows could only mention that brutality in passing. But in the Battlestar Galactica episode "Bastille Day," the connection between the U.S. labor force and the use of prison populations as indentured servants is made graphically clear. Zarek is a terrorist\freedom fighter who is opting to oppose the government, purportedly out of principle, but his opponents claim he is a man obsessed with power. Here is a description of Zerek's political platform, from the episode "Colonial Day""If things weren't so serious, I'd say that was funny. Look, there's no economy. There's no market, no industry, no capital. Money is worthless. And yet, we're all held hostage by the idea of the way things used to be. Look where we are. This man wakes up every morning, tugs on his boots and goes to work in this garden. Why, because it's his job? What job? He labors, but he gets no benefit! And he's not the only one. Many of us are just still going through the motions of our old lives. The lawyers still act like lawyers but they have no clients! Businessmen still act like businessmen but have no business! President Roslin and her policies are all about holding onto a fantasy! If we wanna survive, we need to completely restructure our lives. We need to think about the community of citizens. The group, not the individual. We need to completely free ourselves of the past, and operate as a collective. "

Hmm, sounds suspiciously like a Commie to me, or perhaps some form of anarchist. Collectivized thinking has never been popular in science fiction television, at least since Patrick Mcgoohan's famous Prisoner series, where he proclaimed "I am not a number, I am a free man." While the New Wave made Marxist thinking marginally more palatable to science fiction readers (see the left leaning works of Norman Spinrad and China Mieville ), science fiction has generally leaned right-libertarian, with an increasing emphasis on the libertarian aspect since the sixties (Gordon Dickson, H. Beam Piper, Poul Anderson, Greg Bear, Jerry Pournelle, Larry Niven, etc.) Therefore, its encouraging to see a sci-fi series at least discuss socialist ideals in a close to neutral setting, though the series always tends to imply that Zerek's acts of terrorism are unjustified, a position I do not agree with. Terrorrism correctness hampers the whole Zerek plot thread, as Adama and company always have to have the last word in defining why and for what reasons Zerek is in the wrong. At least that's my impression so far, about a third through the series (Hey I didn't have cable).

So, what hot button issues do you wish science fiction television addressed?

Labels:

China Mieville,

Norman Spinrad,

slave labor,

terrorism,

Tom Zerek

Wednesday, January 13, 2010

Privilege : The Ultimate Dystopia

One of my favorite science fiction movies, though its only loosely science fiction, is the film Privilege. Privilege tells the story of rock star Steven Shorter, living in a near-future England. The British state wants to use Shorter as a tool for manipulating the masses, so they force him to change his persona from "rebel" to state and church supporting conformist. Privilege's attack on the mass media is truly awe inspiring. Shorter's trip from pop singer to gospel rocker mirrors that of the contemporary Christian music (CCM) movement. The end rally in the film, which portrays a Britain slipping into fascism, frightens, because it mirrors so closely the rise of conservative youth radical movements like Battlecry and Teen Mania.

One of my favorite science fiction movies, though its only loosely science fiction, is the film Privilege. Privilege tells the story of rock star Steven Shorter, living in a near-future England. The British state wants to use Shorter as a tool for manipulating the masses, so they force him to change his persona from "rebel" to state and church supporting conformist. Privilege's attack on the mass media is truly awe inspiring. Shorter's trip from pop singer to gospel rocker mirrors that of the contemporary Christian music (CCM) movement. The end rally in the film, which portrays a Britain slipping into fascism, frightens, because it mirrors so closely the rise of conservative youth radical movements like Battlecry and Teen Mania.Paul Jones, the star of the movie, was a real rocker and does an excellent job of portraying the manipulated, angsty Shorter. But the real star of the movie is the director, Peter Watkins. Watkins is an amazing director, whose films, such as Punishment Park and War Games were unofficially suppressed in the 60's and 70's because of their explosive political messages. It's time that Hollywood filmmakers from libertarians to conservatives, and socialists to progressives, were as openly politically rebellious as Watkins proved himself to be in the sixties and seventies. Perhaps then, science fiction film wouldn't be stuck with works like Transformers: Revenge of the Fallen.

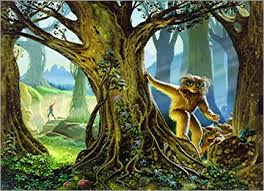

Little Fuzzy: Classic Imperialist science fiction

Pictured to the left is a Fuzzy. One could be forgiven for mistaking a Fuzzy for an Ewok. The two creatures bear a certain similarity, but it was the Fuzzies who first captured the hearts of readers, nearly fifty years ago. The Fuzzy series, consisting of Little Fuzzy, Fuzzy Sapiens, and Fuzzies: The Other People told the tale of cute alien teddy bears who were being exploited by various corporate and political interests on the planet Zarathustra and the effort of brave humans (read: whites) to save the Fuzzies from exploitation. What makes the series so delightful, but also so politically incorrect, is that the Fuzzies (read: Native Americans) are treated like huggable children who need to be protected by the big White Man in the Sky. Even the hero's Fuzzy name, Pappy Jack, implies his Father image among them.

The huggable Native American is actually a fairly common trope in science fiction. There were the Hoka of Poul Anderson and Gordon Dickson, the aliens of Battle for Terra, and the Ewoks of Return of the Jedi. What makes Native Americans and their alien offspring so delightfully huggable to white people? Do we have a secret yearning to be forgiven by our oppressed populations and taken back into the arms of the Native Mother? Or perhaps such portrayals are just the natural outgrowth of a century of colonial narratives, reaching from Star Trek's "The Apple" to Doctor Who's "The Power of Kroll" to Orson Scott Card's Speaker for the Dead and James Blish's Case of Conscience. What do you think?

Labels:

Fuzzy,

imperialism,

Little Fuzzy,

Native Americans

Class in Science Fiction Television

For all its supposed racial liberalism, science fiction television has done a relatively poor job of addressing class issues. Farscape, Star Trek: The Next Generation, Doctor Who, Star Trek: Voyager, and Space 1999 all had nearly zero class analysis in their plots. The original Star Trek series "Cloud Minders,"

For all its supposed racial liberalism, science fiction television has done a relatively poor job of addressing class issues. Farscape, Star Trek: The Next Generation, Doctor Who, Star Trek: Voyager, and Space 1999 all had nearly zero class analysis in their plots. The original Star Trek series "Cloud Minders,"pictured to the left, is probably the most direct class analysis ever done by science fiction. It's one of the few science fiction TV episodes to question the nature and purpose of capitalism. While Star Trek ultimately came down on the side of capitalism, the "Cloud Minders" episode clearly implied that the workers were right in making demands for better pay and equipment. Unfortunately, Star Trek's insistence that poverty would disappear in the future ended up serving as a way of erasing working class people from the Star Trek universe. That universe is comfortably middle class, really upper middle class, with no discernible analysis as to how the Federation managed to achieve this poverty-less society. The Marquis, featured in later episodes of DS9 and Voyager at least showed us that Federation colonial policy wasn't all it's cracked up to be.

Babylon 5 did a somewhat better job of dealing with class. Security Chief Garibaldi clearly was a grunt, a guy who had seen better days. And two episodes, "A View from the Gallery" and "By Any Means Necessary" dealt with working class laborers and the issues they dealt with, including oppressive corporate bosses. Earth 2 was also fairly nuanced in its view of labor strife, not picturing a perfect future, but one in which class strife was epidemic. Battlestar Galactica (the reboot) pictured future humans using slave labor forces, as did Blake's Seven, so neither series could be accused of painting a bright picture of the industrialist class. Unfortunately, today, class is too often relegated to the background, in favor of simplistic analyses of race issues that usually end up condemning racial and ethnic minorities more than helping them. Science fiction television still needs a Marxist classic to match the fifty capitalist classics it has given us.

Labels:

Blake's Seven,

class,

Earth 2,

labor unions,

Marxism,

Star Trek

Tuesday, January 12, 2010

Mutoids and the Ethics of Genetic Engineering

The woman in the picture is a Mutoid, a genetically modified human being from the Blake's Seven series, who is made vampiric through her modifications. One thing I especially appreciate about Blake's 7 is that it always challenges the core assumptions of the "heroic" cast. In the episode from which this is taken, Duel, Blake and Commander Travis are forced to engage in a fight for survival because both men are considered ideological fanatics by the two powerful priestesses who have captured them. Though Blake is clearly seen as the better of the two individuals, the program does not let him off the hook, rightly pointing out that in some ways Blake is like a terrorist. 30 years before John Crichton carried a nuke

The woman in the picture is a Mutoid, a genetically modified human being from the Blake's Seven series, who is made vampiric through her modifications. One thing I especially appreciate about Blake's 7 is that it always challenges the core assumptions of the "heroic" cast. In the episode from which this is taken, Duel, Blake and Commander Travis are forced to engage in a fight for survival because both men are considered ideological fanatics by the two powerful priestesses who have captured them. Though Blake is clearly seen as the better of the two individuals, the program does not let him off the hook, rightly pointing out that in some ways Blake is like a terrorist. 30 years before John Crichton carried a nukeinto the Scarran council chamber, Blake was making one small stride for terrorists everywhere.

But I digress. I wanted to talk about genetic engineering and the Mutoids. The Mutoids are hardly positive characters - they prey on humans for their blood except when constrained by the Federation. Yet, the portrayal of the genetically engineered in Blake's 7 is a positive advancement on similar portrayals in Star Trek (1966-68). In Star Trek, Khan Noonian Singh and his followers are depicted as barbarians who the Federation has a moral right and duty to discriminate against, on the basis of their dangerous "genes". The Mutoids, on the other hand, show the dangers of such discrimination. As a species, they are preyed upon by the Terran Federation (not the UFP), because of their genetic vulnerabilities. Indeed, I don't know that American sci-fi has yet attempted a morally neutral analysis of genetic enhancement technology, as it is too often lumped together with Nazi eugenics policies. Therefore, it's quite interesting to see how British and American science fiction contrastingly show the enhanced as victims (Blake's 7) and victimizers (Star Trek). Who, ultimately, is right?

Introduction to My blog

For all those who have read me from Against Biblical Counseling, this is my fun blog, that I will update periodically. On it, I talk about issues of race, class, sex, gender, religion, etc. as they pertain to science fiction. The picture from the left is of one of my favorite science fiction shows, Blake's 7. I am one of the few Americans under 30 whose even heard of the show (and I won't be under 30 for much longer). Blake's Seven was trendsetting in its approach to political issues. What really set it apart was that the Che Gueverra like good-guy, Blake, was often in the wrong, a trait not seen in American science fiction till Farscape and Firefly (two other shows that I like). Blake's 7, more than any other series, set the bar for the series to come after and so far that, here's a big "cheers" for rebel Blake, thief Vila, cynic Avon, and the rest of Blake's motley crew. Too bad they don't produce science fiction like this anymore.

For all those who have read me from Against Biblical Counseling, this is my fun blog, that I will update periodically. On it, I talk about issues of race, class, sex, gender, religion, etc. as they pertain to science fiction. The picture from the left is of one of my favorite science fiction shows, Blake's 7. I am one of the few Americans under 30 whose even heard of the show (and I won't be under 30 for much longer). Blake's Seven was trendsetting in its approach to political issues. What really set it apart was that the Che Gueverra like good-guy, Blake, was often in the wrong, a trait not seen in American science fiction till Farscape and Firefly (two other shows that I like). Blake's 7, more than any other series, set the bar for the series to come after and so far that, here's a big "cheers" for rebel Blake, thief Vila, cynic Avon, and the rest of Blake's motley crew. Too bad they don't produce science fiction like this anymore.

Subscribe to:

Comments (Atom)